Article published in the journal of the French Harp Association (AIH), n°45 AH/2007

Revised and expanded in March 2020

EN | FR

The Pleyel Harps

Rare are the instrument makers whose names, forever engraved in the history of music, remain as highly regarded as the most famous composers and performers. For two hundred years, the Pleyel firm has been contributing to the French musical world and its international reputation: from Ignace Pleyel’s first instruments, to the recent reopening of the concert hall in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. If the Pleyel adventure is first and foremost that of the piano, it is all too often forgotten that the firm also produced pedal harps - also before the story of the Chromatic Harp began.

Beginnings.

Antoine Vestier - Portrait of Ignace Joseph Pleyel

Ignaz Joseph Pleyel was born in 1757 in Ruppersthal, Lower Austria. His musical talents enabled him to study for five years with the great master Joseph Haydn, becoming his most famous pupil. Ignaz then moved to Strasbourg, where he assisted the Kapellmeister Franz-Xavier Richter. In this way, he adopted French nationality, and became Ignace Pleyel. The European capitals adored the excellent pianist - sometimes comparing him to his former master, which never altered their deep friendship. In Strasbourg, Ignace Pleyel entered into the lucrative business of music publishing, and in 1793 he had Erard pianos sent to him, probably to sell them on. On leaving Strasbourg in 1795, Pleyel opened a sheet music shop in the Chaussée d'Antin district of Paris. He published his own works, and also those of Mozart, Haydn, Boccherini, Méhul, Beethoven, etc. He was the first, in 1802, to launch a collection of pocket scores, the "Music Library", at a competitive price.

A prolific composer, he wrote a vast quantity of works unjustly neglected today: more than 40 symphonies, 60 string quartets, two operas, and countless sonatas and piano trios. Composing even saved his life: he escaped the guillotine thanks to his Hymn to Freedom, which he wrote with Rouget de l'Isle. In 1805, Pleyel became the associate of the piano maker Charles Lemme [1]. Pleyel put down the money, and Lemme his savoir-faire. Their collaboration was a brief one, and then Pleyel set up his own workshops.

In 1807, Ignace Pleyel founded his own company. He did not expect the long and brilliant career that awaited him, in France and far beyond. He had difficult beginnings: if Ignace Pleyel was a brilliant artist, he was undoubtedly less of a manager, and the business would probably have collapsed without the interventions of Méhul and other generous musicians. It seems he had already gone into harp production (or perhaps simply distribution) before 1807, when his wife had tried to dissuade him from founding the company: "Believe me my darling, instead of all these pianos, harps, etc... we would do much better to make all sorts of small things that are in demand every day, that do not require large advances, and which offer sure returns".

His wife’s supplications did not stop Ignace. Despite the support of the great pianist Frédéric Kalkbrener [2], in 1813 he wrote to his son Camille: "Business is going extremely badly, I have sold neither pianos nor harps, not even a poor guitar”. It was precisely that same year that Camille began working in his father's business. At the age of 25, he became Ignace’s authorised representative for all commercial activities.

Camille Pleyel (Alain Roudier Private Collection)

Like Ignace, Camille Pleyel (1788-1855) was an excellent musician. He first studied music with his father, then with the composer Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760-1812) (whose little sonatas are well-known among harpists). Camille proved to be a wonderful performer, as Frédéric Chopin testified: « There is only one man today who knows how to play Mozart, and that is [Camille] Pleyel. When he is willing to play a four-handed sonata with me, I take a lesson ».

Camille travelled, discovering and observing the most fashionable pianos of the time. These included particularly Broadwood pianos in London, some of whose innovations Camille would retain for his own pianos. A better manager than his father, he got the company out of hot water several times. In 1824, he completely reorganized it: joining forces with Kalkbrener, who had just returned from a triumphant tour of Germany with the virtuoso harpist F.-J. Dizi. In addition, Camille Pleyel maintained privileged relations with many influential musicians, such as Cramer and Moscheles, who actively contributed to the promotion of Pleyel instruments.

But it was really in the following year, 1825, that Pleyel manufacture really began. Camille took over the management of the company. In 1827, Pleyel received its first gold medal at the French National Exhibition of Industrial Products, which contributed greatly to its growth.

I. The Pleyel Pedal Harp

It was probably Kalkbrener who introduced François-Joseph Dizi (1780-1840), when the latter arrived in Paris, to Camille Pleyel. The Belgian harpist, professor of Elias Parish-Alvars, and whose collections of études are still much-used by today's harpists, had met Sébastien Erard in London. Erard easily converted him to the double movement system. In London, Dizi also met harp maker Edward Dodd (1791-1843), who made him an unusual double-movement harp on which the strings pass through the centre of the console - a copy is kept in the Musée de la Musique in Paris. Dizi's music is published by Pleyel, in particular the Grand Duo for harp and piano op. 82, written with Kalkbrener.

On various occasions, Dizi reflected on the resistance of soundboards. Purely experimentally, he had a soundboard made of spruce plywood, with horizontal fibres glued against the vertical fibres of a harder wood. Against all expectations, and contrary to all received ideas, the sound practically doubled in power.

Camille Pleyel experienced this himself on a piano, with a double sound board, fir against mahogany. The result was just as surprising, and he patented it with Dizi in 1830.

harpe Dizi-Pleyel, 1830, double mouvement, table d’épicéa doublé d’érable moucheté.

The harps of the Camille Pleyel era can be easily recognized by the curvature of their soundboard in the bass register, elegantly joining the top of the base of the harp according to Dizi's patent (and already also done on some Dodd harps). Pleyel’s harps could be single- or double-action. Contrary to the external mechanism of Erard harps, the Pleyel mechanism was totally internal, foreshadowing our modern harps.

The Empire style of this harp is not far removed from that of some Erard, Erat, Barry, and other harps of this period. The elegant column is finely fluted, with a light golden leaf pattern. The feet appear a little oversized, shaped like lions’ paws.

Like many harps at the time, Pleyel harps are often equipped with the reinforcement system devised by Krumpholtz and made by J.-H. Naderman in 1785. An eighth pedal opens or closes flaps behind the body, thus reinforcing the volume of the harp.

Today, Camille Pleyel’s refined and graceful pedal harps are all the more rare since they have only been produced, in comparison to pianos, in very small quantities. It is difficult to know exactly how many have been sold, as the surviving Pleyel registers only list 75 serial numbers. This does not mean that there were actually so few - far from it, especially with the title of « facteur du roi » (harp maker to the King).

In 1829, father and son founded Ignace Pleyel et Compagnie, with Kalkbrener. This company exclusively manufactured and sold harps.

In 1831, King Louis-Philippe granted Ignace the title of Piano Maker to the King, and Camille the title of Harp Maker to the King. Ignace died in 1831 (so did Sébastien Erard), leaving all Pleyel productions to his son.

In 1834, Camille received a new gold medal at the National Exhibition of French Industrial Products, and another silver medal with Dizi for harp manufacture.

Like Ignace Pleyel and Sébastien Erard in the past, Camille Pleyel died the same year as Pierre-Orphée Erard, Sébastien's nephew and director of the Erard House in London - in 1855.

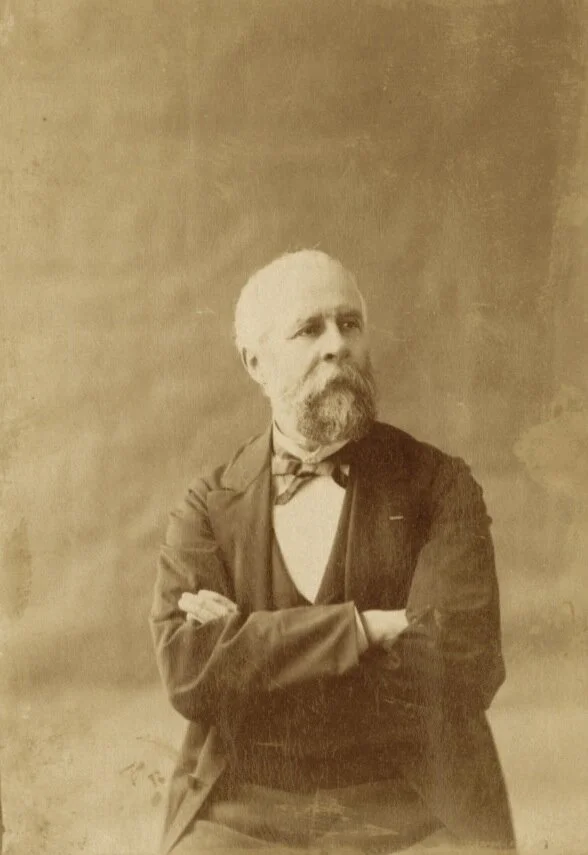

Auguste Wolff

Auguste Wolff (1821-1887), who had been Pleyel’s business partner for two years, took over. A good pianist and composer himself, and the nephew of Ambroise Thomas, he gave the company a new lease of life, and many happy years. During the Wolff years, Pleyel pianos benefited from many important innovations, but as soon as he arrived, it stopped making harps for good.

Despite the impressive agility and virtuosity of many harpists (Dizi, Bochsa, Labarre, Parish-Alvars...), and no doubt annoyed by the conflict between Naderman's old single-movement harps and the new double-movement system, Wolff saw principally the pedal harp’s imperfections. Anxious to leave only perfect instruments (or at least, those that could be made so), he finally decided to destroy all Dizi & Pleyel harps [3]. In the courtyard of the Pleyel building in the Rue Rochechouart, he burned more than 200,000 francs worth of harps that had been completed or were in production, as well as all the material used in their manufacture.

Thus the production of Pleyel pedal harps ceased definitively in 1855.

When it came to the piano, Wolff's main concern was reliability and solidity. His most important contribution is undoubtedly the metal frame, which is reinforced by several bolted, interlocking metal bars. Presumably to reassure pianists and their negative prejudices about the bad influence of metal on sound quality, he referred to his cast iron frame firstly as “bell” or “bedspring” bronze; then ”Pleyel steel”, a term that alone was enough to guarantee its excellence.

Wolff developed new piano models, including the famous small model, 1.5 metres long, which Charles Gounod called the “toad”. He also invented the pianino, a very popular small upright piano. It had a version which could be dismantled, the “passe-partout” (“go everywhere”), which could be carried on the back of a mule.

Alibert pegs

Wolff patented a new system of string fasteners in 1875, the Alibert pegs, named after their designer. These micrometric screw pegs were specially made so that the pianist himself could replace a broken string and tune it without too much difficulty. To the main pin, blocked by a rack, a smaller one at the back of the string was added. This made it possible to refine the tuning by modifying its angle. To offer pianists more comfortable space for the tuning key, these pegs are not located on the keyboard side, but at the other end of the frame! However, the thinness of some parts of these pegs made them relatively fragile. Together with their inconvenient location, it is easy to imagine that the tuning of this type of piano remained a bit perilous for a layman. In spite of their ingenuity, the Alibert pegs were quickly abandoned. However, a similar idea was taken up again in the 1920s, for violin fine tuners on the tailpiece.

Wolff also invented a number of improvements more or less still used today, such as the transposing keyboard, or the ancestor of the sostenuto pedal. He also proved to be an excellent company director, with a very paternalistic management, as it is common in large companies..

The firm prospered and became a true model of French industry - by the death of Auguste Wolff, it had more than 600 employees. Throughout the Wolff period, Pleyel was to sell more than 73,000 pianos, an average of more than 2,200 per year. The Pleyel harp, however, was but a distant memory.

When Auguste Wolff died in 1887, his son-in-law and long-time collaborator Gustave Lyon took over. This marked the beginning of what many consider to be the best years at Pleyel, the years that contributed so much to the legendary myth of the manufacture

Gustave Lyon (1857-1936) was not himself a performer - unlike his predecessors. A former student of the Ecole Polytechnique and a government-certified engineer, he put all his scientific knowledge to the service of music, in particular the piano.

His most important revolution was probably the improvement of the piano frame, no longer made of bolted and assembled cast iron, but cast in one piece (Steinway had already adopted this method in 1867).

He also created the legendary F Model grand pianos, the P and 9 upright pianos, the piano with two keyboards facing each other, and the Pleyela mechanical piano. He invented the molyphone, a system where additional strings are used only for resonance by sympathy, without ever being struck.

In 1890, the Pleyel grand piano n°100.003 made for Villa-Lobos is equipped with this system. The extra strings were attached to the famous Alibert pegs, easily tunable.

1. Charles Lemme (1769-1732), originally from Braunschweig, a clavichord and piano maker, settled in Paris in 1799.

2. Frédéric Kalkbrenner (1785-1849) was a pianist and pedagogue of great renown in his time. He was also a friend of Haydn and Clementi, and their influence can be perceived to some extent. He is the author of an abundant body of work, now forgotten: sonatas, concertos, and numerous pieces of chamber music.

3. The future director of Pleyel, Gustave Lyon, relied heavily on Naderman's criticisms of the double-action mechanism. To take Auguste Wolff’s defence on this subject of 1855, he speaks, curiously, of the "Pleyel-Dizi and Naderman" harps. Franz Joseph Naderman died in 1835, and there does not seem to have been any such prior collaboration, whether with Dizi, Ignace or Camille Pleyel. In the past, Franz Joseph Nadermann had often and rather virulently challenged Erard's double-action system: a professor at the Paris Conservatory, he himself made harps. These were all single-action instruments, like his father Jean-Henri Naderman’s - the famous harp maker of Queen Marie-Antoinette. It therefore seems unlikely that the "curator" F.J. Naderman would have associated himself with a house as avant-garde as Pleyel (with its single and double-action harps) and, above all, a competitor of his own.